The new issue of THE ECONOMIST includes an article that just blew me away. It's about the latest research on all the microbes that live in your gut.

Your body harbors 100 trillion bacteria, ten times the number of cells you grew from your DNA, containing 3 million genes. And they are yours: Humans differ vastly, it turns out, in the composition of this microbiome. Some people have more of one kinds of microbes, other people have more of other kinds. This has vast implications for health, most of which are just beginning to be explored. Some findings so far:

Overweight people have more Firmicutes and fewer Bacteroidetes than thin people. The later suppress the making of a hormone that facilitates fat storage, which is part of why Sally can eat a pint of Haagen-Dasz and not gain an ounce and Molly puts on three pounds looking at a picture of one M&M.

Twin studies carried out by the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis show that even on the exact same diet, one twin can develop malnutrition and the other not, depending on their individual gut bacteria.

Formic acid produced by gut bacteria can contribute to heart disease, because formic acid signals to the kidneys how much salt to absorb back into the body or to excrete with urine. Too much salt can damage arteries.

Scientists are also investigating possible links between gut bacteria and diabetes type 2, MS, and even autism.

Most amazing to me is the case of C. difficile, a bug that causes severe diarrhea, killing about 14,000 Americans each year. Many strains have evolved resistance to even last-ditch antibiotics like vancomycin and metronidazole. Worse, when these are tried, they kill off most of the patient's gut microbiome. But at the Baptist Medical Center in Oklahoma City, doctors have come up with a successful--if gross--way to combat resistant C. difficile. They give patients enemas with feces from healthy adults. The new bacteria take over the gut and kill off the infection.

I have written stories about the evolution of disease microbes (including "Evolution," in my mini-collection THE BODY HUMAN, from Phoenix Pick). The bacteria have an advantage in the medical arms race: They can evolve a new generation every twenty minutes, swapping plasmids to beef up each other's resistance to our drugs. But we have brains on our side. Despite the recent terrible onslaught of hospital-bred infections at NIH, there is lots of room for hope. This excellent article illustrates why.

Sunday, August 26, 2012

Tuesday, August 21, 2012

Cranky at the Theater

Last week I saw a production of the Tony-winning musical RENT, at Seattle's Fifth Avenue Theater. It was a good production, slightly made-over from the 1980's version, with terrific actors. Some of the music is appealing, especially "Seasons of Love."

However, the rock opera left me unsatisfied. My three companions didn't share my reasons, so maybe it's just me. I suspect, however, that since individual experience strongly affects one's reaction to art, and I am just too old for RENT.

Based on the nineteenth-century opera LA BOHEME, RENT concerns a bunch of would-be artists living in the East Village. In LA BOHEME some of them were dying of consumption; in RENT, it's AIDS. There is an on-stage death scene which is moving, as one character loses his drag-queen lover. My problem was not with any of that, but with the underlying assumptions about the Bohemian life: it's much better than any stodgy bourgeois existence; it produces "real" artists because earning money corrupts people; the young artists are all superior to their frantic parents, who phone them from concern that the kids are all right; artists have the right to occupy their lofts without paying the landlords any rent because, well, they're artists.

None of this seems true to me. Worse, it seems affected, exploitative, and even pathetic. Many artists have produced wonderful work while living bourgeois lives. Some even went on producing after they'd made money. Landlords have taxes to pay on their buildings and children to feed. Not everyone who works in, or even is, a corporation is despicable. And parents deserve a break in their anxiety for their kids, in the form of a few phone calls now and then.

So I left the theater cranky. And definitely too old for this show. I wanted to say to everyone on stage: Just pay your damn rent!

However, the rock opera left me unsatisfied. My three companions didn't share my reasons, so maybe it's just me. I suspect, however, that since individual experience strongly affects one's reaction to art, and I am just too old for RENT.

Based on the nineteenth-century opera LA BOHEME, RENT concerns a bunch of would-be artists living in the East Village. In LA BOHEME some of them were dying of consumption; in RENT, it's AIDS. There is an on-stage death scene which is moving, as one character loses his drag-queen lover. My problem was not with any of that, but with the underlying assumptions about the Bohemian life: it's much better than any stodgy bourgeois existence; it produces "real" artists because earning money corrupts people; the young artists are all superior to their frantic parents, who phone them from concern that the kids are all right; artists have the right to occupy their lofts without paying the landlords any rent because, well, they're artists.

None of this seems true to me. Worse, it seems affected, exploitative, and even pathetic. Many artists have produced wonderful work while living bourgeois lives. Some even went on producing after they'd made money. Landlords have taxes to pay on their buildings and children to feed. Not everyone who works in, or even is, a corporation is despicable. And parents deserve a break in their anxiety for their kids, in the form of a few phone calls now and then.

So I left the theater cranky. And definitely too old for this show. I wanted to say to everyone on stage: Just pay your damn rent!

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

Three Girls

In the last few weeks, due to much time on an airplane and even more time not feeling well (I always seem to get sick after flying), I read three novels. All three have spent time on the NEW YORK TIMES bestseller list, although not the same amount of time and not in the same year. All three center on a young woman in a problematic relationship.

THE NEWLYWOODS chronicles the Internet courtship, marriage, and emigration to America of Amina, an educated but poor Bangladesh woman who wants a better life. She doesn't love George, her new American husband, but she likes him well enough, and she needs him to bring her parents out of danger in her native country. Amina's relationships--with George, with the old love she left behind, with her parents and extended family, with her new American relatives, and with the United States itself--grow increasingly complex as the novel progresses. Her choices grow harder. Whether or not you agree with Amina's final decision, she is believable, interesting, and very human.

The third book I read was E. L. James's FIFTY SHADES OF GREY, about Anastasia Steele and everybody-already-knows-what. The less said about this novel, the better -- except for one question. Why is the book about a believable young woman struggling with genuine, and genuinely complex, moral and family issues the least commercially successful of the three; the second-best book much more successful; and the trashy one dominating everything from bookstores to social commentary? What does that say about us, the book-buying public?

THE NEWLYWOODS chronicles the Internet courtship, marriage, and emigration to America of Amina, an educated but poor Bangladesh woman who wants a better life. She doesn't love George, her new American husband, but she likes him well enough, and she needs him to bring her parents out of danger in her native country. Amina's relationships--with George, with the old love she left behind, with her parents and extended family, with her new American relatives, and with the United States itself--grow increasingly complex as the novel progresses. Her choices grow harder. Whether or not you agree with Amina's final decision, she is believable, interesting, and very human.

A little more formulaic but still very good is Philippa Gregory's historical novel, THE VIRGIN'S LOVER. Amy Dudley is the young wife of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, who has the good fortune to be having a love affair with the young Queen Elizabeth I. Not such good fortune for Amy. History has offered several opinions on how Amy Dudley ended up dead at the bottom of a staircase four centuries ago, but Philippa Gregory offers a fresh, absorbing take on this, along with her usual vivid picture of Tudor England. Amy Dudley here is not as complex or solid as Amina Stillman, but the novel is still very good

The third book I read was E. L. James's FIFTY SHADES OF GREY, about Anastasia Steele and everybody-already-knows-what. The less said about this novel, the better -- except for one question. Why is the book about a believable young woman struggling with genuine, and genuinely complex, moral and family issues the least commercially successful of the three; the second-best book much more successful; and the trashy one dominating everything from bookstores to social commentary? What does that say about us, the book-buying public?

Friday, August 10, 2012

Young Adult Fiction

Over a year ago I attended a panel on YA fiction, and something I heard has picked at my mind ever since. This particular panel consisted of librarians, both school and public, talking about what young people read. They had discussed the usual suspects and the panel was open to questions. I asked about a recent award-winning YA book, science fiction, that had garnered amazing reviews. The librarian smiled sadly. "We recommend it, but most kids start and then abandon it. They say it's too slow and not exciting enough."

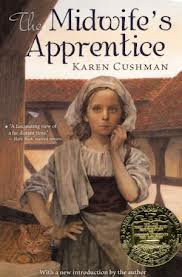

I have heard this before about other award-winners, including recipients of the prestigious Newberry Medal. I have just finished reading THE MIDWIFE'S APPRENTICE, a book by Karen Cushman, who previously had won a Newberry for CATHERINE, CALLED BIRDY.

Both books are set in the Middle Ages, and although the world they depict has its share of brutality, the books' two heroines, one a young lady and one a homeless village girl, don't engage in much derring-do. There is no magic. No sword fights, no quests, no battles, no deaths except from natural causes. "We recommend Karen Cushman," the librarians said, "but mostly those books are read aloud to classes by teachers."

All this has raised a question in my mind: Do kids consistently choose different books for themselves than adults would choose for them? Is that why Harry Potter and Katniss Everdene, but not Catherine called Birdy, became best-selling icons? And if what constitutes a really, really good book is not the same as judged by adults and by kids, then which should a writer be considering in shaping his or her story?

I have a YA novel coming out in November: FLASH POINT, from Viking. I wasn't much aware of this question while I was writing it. And now I don't know the answer--or how much appeal the novel might have to either audience--although it seems to me that I was trying for both. Now I'm wondering if that may have been a mistake, in that it may not be possible. The things they want in fiction seem very different.

I have heard this before about other award-winners, including recipients of the prestigious Newberry Medal. I have just finished reading THE MIDWIFE'S APPRENTICE, a book by Karen Cushman, who previously had won a Newberry for CATHERINE, CALLED BIRDY.

Both books are set in the Middle Ages, and although the world they depict has its share of brutality, the books' two heroines, one a young lady and one a homeless village girl, don't engage in much derring-do. There is no magic. No sword fights, no quests, no battles, no deaths except from natural causes. "We recommend Karen Cushman," the librarians said, "but mostly those books are read aloud to classes by teachers."

All this has raised a question in my mind: Do kids consistently choose different books for themselves than adults would choose for them? Is that why Harry Potter and Katniss Everdene, but not Catherine called Birdy, became best-selling icons? And if what constitutes a really, really good book is not the same as judged by adults and by kids, then which should a writer be considering in shaping his or her story?

I have a YA novel coming out in November: FLASH POINT, from Viking. I wasn't much aware of this question while I was writing it. And now I don't know the answer--or how much appeal the novel might have to either audience--although it seems to me that I was trying for both. Now I'm wondering if that may have been a mistake, in that it may not be possible. The things they want in fiction seem very different.

Thursday, August 2, 2012

Round-up of Miscellaneous Stuff

Oz Drummond, who runs the Writing Workshop at Worldcon, has asked me to say that there are still slots open at the workshop. If you are going to Worldcon, have your ms. critiqued by a pro! Gerry Nordley and I will be leading one session.

On August 9, I'm reading at the University Bookstore in Seattle at 7:00 p.m. Not sure as yet just what I'm reading. Novel in progress? Maybe.

As I type this, the Blue Angels are practicing outside my on-a-hill-and-sixth-floor window, over Elliot Bay. They perform this weekend for SeaFare, in Seattle. They are impressive, and VERY loud.

My toy poodle, Cosette, after her last grooming. This photo would seem cuter to me if I didn't know that she bit the groomer.

On August 9, I'm reading at the University Bookstore in Seattle at 7:00 p.m. Not sure as yet just what I'm reading. Novel in progress? Maybe.

As I type this, the Blue Angels are practicing outside my on-a-hill-and-sixth-floor window, over Elliot Bay. They perform this weekend for SeaFare, in Seattle. They are impressive, and VERY loud.

My toy poodle, Cosette, after her last grooming. This photo would seem cuter to me if I didn't know that she bit the groomer.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)